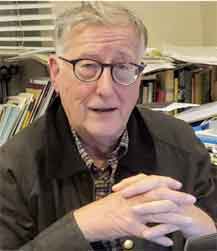

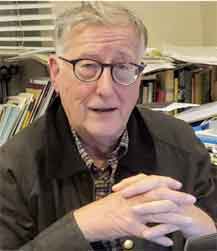

Summerhall's Robert Macdowell

The ground breaking arts centre Summerhall has undergone radical upheaval in recent months. Maxwell Macleod sits down with its founder

|

|

EDINBURGH'S threatened Summerhall is now one of the biggest privately owned art centres in Europe. Based in vintage former university buildings and still only fourteen years old, it now provides resources for hundreds of art workers everyday in its theatres, studios, restaurants and out leases.

However during the last year many of its own administrative accounts have been frozen by the tax authorities in controversial disputes usually conducted over the phone.

Whilst not being privvy to details to many of these disputes ArtWork felt it right to offer a platform to Summerhall's founder and manager Prof Robert Macdowell and here what follows is based largely on a conversation with him shortly before we went to press and which we allowed him to broadly edit.

|

IT'S SIX P;CLOCK on a March evening and the once rumbustiously noisy Summerhall art centre is strangely quiet. The main phone seems to be off the hook and whilst the pub is busy there seems to be very little else happening.

The old Edinburgh Dick Veterinary School as it looked when taken over by the Summerhall operation. Transformed into a highly popular pub at its heart.

A shadow seems to have fallen on a light that was once so invaluable to Edinburgh's art scene. I rudely knock uninvited on the door of the director Macdowell and offer him an article in ArtWork written by him. He refuses, saying he is still too angry but will broadly edit one by me based on an interview. I should admit that on this final draft I made a few later additions, though the core that he approved is unchanged.

On my arrival at Robert's office he is as usual polite and welcoming. We are not really friends but after watching him for fourteen years as he has. conceived, built and managed Summerhall I know him to be straight and honest and hold him in respect and with a genuine affection.

He looks terribly tired and wanders off to get a dry croissant. We then discuss Trump and in spite of his eighty odd years, Robert seems informed and cogent and in good shape for a man of his years.

I observe that given all that Summerhall has done for the arts it would seem a pity that so much of the tax issues were resolved on the phone rather than through the face to face visits which might have been more sympathetic and understanding.

In response he lists the millions in taxes that he had to pay to unfreeze his bank accounts and allow any discussion on the issues, but expediently comments no further.

Robert may have his faults but he is a creative leader rather than an administrator, though with a good team behind him

"Where are we now?" I ask.

"Well they have set up a charity to run the events, I am to have little to do with it."

He then looks away. There is a long pause. He reminds me of a decent father who has just lost his child Truly this man deserves more plaudits, though I suspect he may still have an important role to play in a new style Summerhall.

He observes how many don't understand that many work in the arts for little or even no money and estimates as an example that the average Fringe actor will lose around two thousand pounds during the Festival

He goes on to say that many leaders in the arts are underappreciated, and I reply that he himself should get a peerage for what he has done with Summerhall, at which he scoffs.

"A medal then?" I suggest? He offers a smile that is rare for the day.

As I leave I think that I still don't understand what's been going on at Summerhall, but still admire Robert. whatever his part in its troubles may or may not have been.

As I walk home I think what an amazing achievement the first phase of Summerhall has been and worry a bit for the next, possibly less altruistic one.

Truly these places need inspirational leaders more than penny counters. As they may yet find out. Suddenly I remember I have foolishly left my crash helmet on Robert's desk.

Maybe Robert might have been wiser to ensure he had one for himself.