The world of wood faggotters, yowlers and biscuit-oddmen…

Nick Jones has been meeting some of the practitioners in James Fox's masterly account

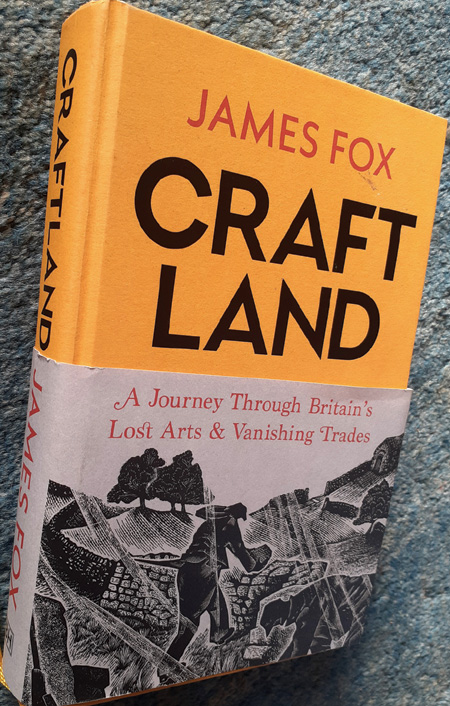

Craftland ISBN 9781847 927 866 The Bodley Head UK Price £25

YES, this Journey Through Britain's Lost Arts and Vanishing Trades by James Fox is primarily about the importance of making by and with human hands, blessed with opposing thumbs, enabling us to manipulate and grip. But also the triumph of the human spirit – obsessive, determined, perfectionist, bloody-minded.

James is Creative Director of the Hugo Burge Foundation at Marchmont, near Duns, where the foundation provides studios for artists, makers and artisans. His passion for and commitment to supporting and encouraging the crafts is clear. He describes in fascinating detail how surnames confirm that our forebears were makers - Smith, Wright, Taylor, Mason - it's a long list. Funny, sometimes ribald too: biscuit-oddman, bumboat man, butt woman, wood faggotter and yowler.

Our language is equally revealing. Ringing clear as a bell through this remarkable journey are characters who don't give a damn about time, or money, or creature comforts. Their aim? To learn, practiise and perfect their trade; to make artefacts which are useful, durable, and beautiful; and to enjoy making them. Critical to many are local materials.

This connection with place makes economic, ecological and emotional sense, especially if materials are abundant and free. James travelled from remote Highlands to Isles of Scilly to find these people. Many have no interest in being seen, known or, Heaven Forfend, adulated. They just want to get on with their demanding, painstaking, time-consuming, highly skilled work. Mistakes and setbacks are par for the course. There are no shortcuts.

The book divides into three sections. The first, Landscape, covers dry-stone walling in Yorkshire, thatching in Wester Ross, chair-bodging in the Chilterns, and rush-weaving in Bedfordshire.

In the second, Community, James tracks down the last major oak bark tannery in Britain, and, over the river, a master wheelwright, both in Colyton, Devon. Next comes basket making for fishermen in Devon, Cornwall, and the Isles of Scilly. Then he's off to Loughborough, home to Taylors, Britain's only extant bell foundry, to meet their Gujarati tuner, one of few worldwide with the skill and patience for this exacting calling. Then to Cambridge, to the Cardozo Kindersley letter-carving studios, creating plaques, memorials, signs and headstones. Apprenticeship demands a complete change of attitude to time, being in the moment and never, ever, hurrying a job.

In the final section, Industry, he describes how Roger Smith, aged sixteen, determined to be a bespoke watchmaker. He spent eighteen months making a watch to show the great horologist George Daniels, who told him to start again. He did. Now, a Roger T Smith watch costs a seven figure sum, and you may have to wait years. To County Antrim next, home of Bushmills whiskey, and the gentle art of coopering, aka cask-making. Golden rule one: never drink the hard stuff! Then to Sheffield to find out about tool-making, and the putter-togethering of scissors. Cutting paper will never be the same!

In the final chapter, "The Crucible", James is in London, giving the lie to any notion that crafts are restricted to some hazy, bucolic rural idyll. Here he finds multicultural, international, buzzing hives of activity where sofers, scribes of sacred Hebrew texts, produce mezuzahs; where griots, West African troubadours, make ngonis and balafons; and where Japanese potters throw porcelain meipings, plum blossom vases.

Not long ago these traditional trades would have been written off as relics of a bygone age, irrelevant, albeit sometimes quaint, amusing, or instructive. The kind of thing you might see in a museum, junk shop or down the dump.

Each generation has its deities. Today Great AI appears to hold sway, with mysterious binary acolytes like ChatGPT. You know, Generative Pre-trained Transformer, a chatbot, openAI that can walk, talk and make... kind of. Except…

Except that the human spirit, ever resilient, obstinate, crafty even, is making a comeback. Far from being ancient history, "Craftland" is a clarion call, inviting us to wake up, listen, and take note, and make. The past is the future. The crafts are an important part of the creative economy, growing faster than the automative, aerospace, life science and fossil fuel industries combined. Better still, they can change the cycle of consumption and waste.

Most important, as James concludes "They express something too many of us have forgotten: making satisfies a deep and essential need, and so helps us feel truly human."

Published by The Bodley Head. £25.